The struggle over Sumak Kawsay in Ecuador

I wrote this knowing a friend and activist from Junin is illegally being kept in jail for defending his land, his community, the unique environment of Intag's Cloud Forest, and fundamental human rights. The criminalization of social protests here in Ecuador—most of it aimed at environmental protesters—has taken a nasty turn lately, with the illegal dissolving of a well-known NGO, the president of Ecuador publicly insulting activists in nationally televised addresses, and now the outrageous arrest of Javier Ramirez, from Junin. Here's for a wiser Earth Day in 2015!

When I first thought about writing about Sumak Kawsay I was wary of adding to the plethora of ideas surrounding this indigenous concept. Yet, I changed my mind when I saw how little is being said about its potential role in the conservation of the environment, and how it is being grossly distorted by the government in Ecuador.

Sumak Kawsay is a Quechua term. Quechua is the language spoken by approximately 10 million people of the Andean countries of South America. It was spread by Inca conquest during and 15th and early part of the 16th centuries. The simplest definition of Sumak, is good. Kawsay, translates to Life or living. Thus, Sumak Kawsay, in the most straightforward interpretation, means Good Life, or Good Living. In Spanish it is often translated as “Buen Vivir”, or “Vivir Bien”; the latter means “Living Well”

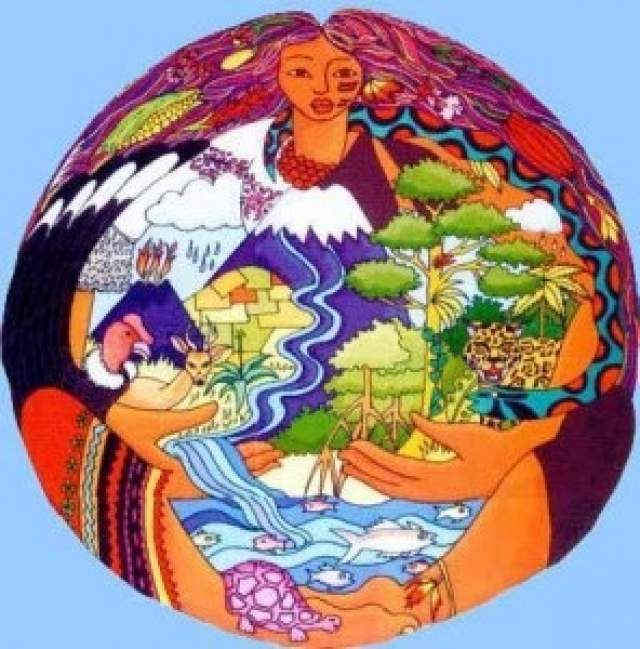

Although there is a fascinating diversity of perceptions of what Sumak Kawsay means, the following one, in my opinion, sums up many of the ideas of both academics and indigenous that gave rise to the concept and enriched its meaning:

In its most general sense, buen vivir denotes, organizes, and constructs a system of knowledge and living based on the communion of humans and nature and on the spatial-temporal harmonious totality of existence. That is, on the necessary interrelation of beings, knowledges, logics, and rationalities of thought, action, existence, and living. This notion is part and parcel of the cosmovision, cosmology, or philosophy of the indigenous peoples of Abya Yala (Walsh 2010: 18).1

The concept was incorporated into Ecuador’s new Constitution in 2008. A slightly different Quechua version was included in Bolivian’s Constitution the following year. In all, Sumak Kawsay, or its Spanish translation, is mentioned 25 times in Ecuador’s Constitution. Most importantly, it is mentioned in the Constitution’s prologue in the context of the country wanting to create “a new form of citizen coexistence, in diversity and harmony with nature, to achieve “living well”, Sumak Kawsay”. The concept has its own chapter with 25 articles describing to Ecuadorians their basic rights associated with it, but no clear definition is given. The rights include the right to live in a healthy environment, rights to education, access to water, freedom of association, and access to health. However, while this sounds fantastic, one Ecuadorian intellectual has soberly pointed out recently that, “Latin America has a long history of seeking judicial perfection without sweating over enforcement.” This appears to be the case in Ecaudor.

The concept, or the government’s version of it, has so taken hold over the imagination of officials that it is repeatedly used to the point of obnoxiousness. So much so, that more and more critics say it has almost completely lost its value as a conservation force, or as a viable alternative to the dominant development paradigm. Not a day goes by in Ecuador that one does not hear of a government Sumak Kawsay plans, forums (both here and abroad), projects, schools, or institution being inaugurated or presented. he idea so captivated officials that it was inserted into the government’s National Development Plan; now called: Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir. Needless to say, the Plan holds impressive contradictions, including promoting large-scale mining as a way of achieving Sumak Kawsay (in fact the slogan for the state-owned mining company is “Mining for Living Well”). But, as another critic pointed out, the 450 page-long National Development Plan is little more than an elegant poem.

Thus, the government has been repeatedly (and rightly) accused of using it as a mere marketing gimmick to promote its “Citizen’s Revolution” rather than taking it seriously and ensuring how to best guarantee people’s right to Sumak Kawsay: a “living well” not based necessarily on an economic-materialistic vision of life and living, as it is being executed in real life in Ecuador, but rather one based on cultural understandings of what that living well means. Given that Ecuador is a Pluri-cultural State, as recognized in the Constitution, it implies that there manifold visions of living well. Monopolizing the concept means killing, or colonizing the concept. Thou Shalt Live Well according to this government’s vision of Sumak Kawsay is colossally oxymoronic. Furthermore, the government’s version is more and more mutating into a capitalist vision—one based on going full speed ahead with opening the whole country to extractive industries.

The opening up of the Yasuní National Park to oil development as well as its aggressive promotion of large-scale mining in environmentally sensitive areas where it is rejected by communities is often used to point out just a couple of the government’s gross distortion of the concept and impressive incoherence between law and reality. In addition, within the Yasuní National Park two indigenous groups live in voluntary isolation from the industrialized nightmare considered in many parts of the world as the “Good Life”, and want nothing to do with oil development.

Where does conservation and Sumak Kawsay fit into all this? Believe it or not, there is a positive side to Sumak Kawsay; and it is one that most indigenous people and more and more campesino communities are taking to heart.

If you look back to the original inspiration for the concept, it comes in great part (and ironically enough) from the example of a few indigenous communities fighting to protect their land, their rights, their environment and their culture from the impacts of extractive development as embodied by mining and petroleum companies. In this context, the decades-old struggle of the Amazonian community of Sarayaku against petroleum development played a key role in inspiring the concept. However, some of the individuals responsible for lobbying for its inclusion in the Constitution insist that the concept is based on much more than the Andean or Amazonian cosmovisions, and encompasses indigenous as well as non-indigenous concepts from other cultures that support a healthier human-nature relationship, social peace, justice, and equality.

When indigenous leaders are asked what Sumak Kawsay means to them, the terms most often used are: co-existence, reciprocity, solidarity, healthy ecosystem, social peace, communal existence, equality, and plentitude. Harmony is often present in their narrative, and it involves harmonious relations not just with Mother Nature, but also with one’s community and one’s self. Harmony within the community is stressed in most accounts. Thus, anything that would risk upsetting that harmony is rejected. Note that neither economic wealth nor material accumulation are mentioned in these accounts. This is one of the reasons the concept has been seized by academics and intellectuals who see it as an alternative model of development to capitalism’s depredation. It is worth noting the contradiction of the government policies

Whether Sumak Kawsay is an alternative vision only to capitalism is open to debate. Nevertheless, I am sure most indigenous cultures would agree with the concept’s anti-capitalist and anti-extractivism connotations.

What is happening is that the more and more Sumak Kawsay is being taken up by both indigenous and non-indigenous communities who are defending their rights against the onslaught of extractivism. Meanwhile, it has been the indigenous movement in Ecuador who were the first to transform it into a powerful force to stop the plundering of their resources, territories, and cultures. But the concept is equally being used by any group that see a healthy environment (both social and natural) as an essential ingredient to a good life. Simply expressed: how can a government guarantee the people’s right to Sumak Kawsay if the projects it promotes endangers the fundamental principles of the concept?

Intag is an example of non-indigenous community’s use of Sumak Kawsay. The struggle against mining development in Intag will be 20 years old this coming January. Even though the term is not widely used in Intag, Intag’s success is partly due to the opposition being able to create a vision of development that excludes mining, and linking that vision to a healthy or “good life.” Our emphasis has been that well-being (Sumak Kawsay), is much, much more than just having more money or things like a bigger home, first-rate roads or better higher education. It is centered on correctly valuing natural, social wealth and cultural wealth, and includes living in a healthy environment, having safe sources of water, harmony in the communities and strong social cohesiveness. Economic wealth is not left out of the picture- and the opposition to mining has been able to create a series of sustainable economic activities, such as shade-grown coffee production and community ecotourism (to mention just two of many). In this vision of life, economic wealth is not shunned, but it is not the guiding principle of life. Community health is much more important, as is a healthy environment. In effect, and without knowing of its existence, what the opposition in places like Intag has been fighting for all these years is to uphold the right to Sumak Kawsay. The fact that it is now recognized as a fundamental Constitutional gives them another tool to aid their struggle.

Intag is an example of non-indigenous community’s use of Sumak Kawsay. The struggle against mining development in Intag will be 20 years old this coming January. Even though the term is not widely used in Intag, Intag’s success is partly due to the opposition being able to create a vision of development that excludes mining, and linking that vision to a healthy or “good life.” Our emphasis has been that well-being (Sumak Kawsay), is much, much more than just having more money or things like a bigger home, first-rate roads or better higher education. It is centered on correctly valuing natural, social wealth and cultural wealth, and includes living in a healthy environment, having safe sources of water, harmony in the communities and strong social cohesiveness. Economic wealth is not left out of the picture- and the opposition to mining has been able to create a series of sustainable economic activities, such as shade-grown coffee production and community ecotourism (to mention just two of many). In this vision of life, economic wealth is not shunned, but it is not the guiding principle of life. Community health is much more important, as is a healthy environment. In effect, and without knowing of its existence, what the opposition in places like Intag has been fighting for all these years is to uphold the right to Sumak Kawsay. The fact that it is now recognized as a fundamental Constitutional gives them another tool to aid their struggle.

This emerging vision of upholding a community’s right to a “good life” was confirmed in a 2012 study carried out in Intag in which 600 women were interview by other local women with the objective of finding out their perceptions on social, economic, environmental and other issues. In the report, published last year, women felt that clean water was indispensable for their vision of a good life, and that the conservation of forests was of vital importance. In fact, 98.8% of the women thought Intag’s forests should be conserved, and that they were essential to guarantee safe water. In addition, over 70% of the women rejected mining as a development option.

At least in Intag, what the report shows is that the basic principles of Sumak Kawsay is alive and well in this region, and that the area’s forests and other natural resources stand a real chance of being conserved. What stands in the way is the government’s version of the concept, which does not value diversity (both cultural and natural) and is intolerant of other versions but its own of what living well means. And that translates to, among other things, pushing oil and mining projects in areas that are anything but apt for those activities, and where most of the population is opposed to them.

This divergence of visions has caused numerous clashes between the Correa government and indigenous and campesinos communities all over Ecuador, which in many cases has led to human rights violations and criminalization of protests and diseent. Over 200 indigenous and campesinos have been criminalized for defending their rights to Living Well during the seven years Correa has been in office.

The latest case of criminalization of protests happened this month when the young campesino leader from Intag and father of four, Javier Ramirez, was jailed after being accused of roughing up an Ecuadorian mining company official, which allegedly took place during a protest to keep the Junín mining project from proceeding. While in police custody, Javier was charged with two other crimes, sabotage and terrorism, crimes that carry 10 or more years prison terms. However, Ramirez was at his home at the time of the alleged confrontation nursing a swollen knee and under doctor’s orders for complete rest. He is the president of the community of Junín, which has been defying an open-pit mining project for nearly 20 years. He is currently serving a 90-day jail term in a prison, and sharing a very small cell with dozens of murderers and rapists while the investigation proceeds to determine whether he was at the scene of the alleged crime and is guilty of what he is accused of. Keep in mind that Ecuador's Constitution considers jail only in exceptional circumstance, and that Javier was not afforded his right to defense when accused and before the arrest warrant was issued.

This is part of the "Ecuadorian Miracle" most outsiders never get to see. So much for Sumak Kawsay…

Carlos Zorrilla lives full time in a farm in Ecuador’s Intag region with his family, and is one of the founding members of DECOIN, a small grass-roots organization that has taken part in the resistance to mining in Intag since its founding, in 1995.

References:

1. El concepto de sumak kawsay (buen vivir) y su correspondencia con el bien común de la humanidad/ François Houtart

2. Good Life As a Social Movement Proposal for Natural Resource Use: The Indigenous Movement in Ecuador. Philipp Altmann, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany

3. El Buen Vivir. Sumak Kawsay, una oportunidad para imaginar otros mundos. Alberto Acosta. 2013

4. Sumak Kawsay Yuyay: Antología del Pensamiento Indigenista sobre Sumak Kawsay. 2014

5. Encuesta de la coordinadora de mujeres de Intag. Coordinadora de Mujeres de Intag. 2012

6. You can read more about this case at: codelcofueradeintag.blogspot.com, and decoin2.blogspot.com

Source: Upside Down World

Categories

Latest news

- LifeMosaic’s latest film now available in 8 languages

- การเผชิญหน้ากับการสูญพันธุ์ และการปกป้องวิถีชีวิต (Thai)

- LANÇAMENTO DO FILME BRASIL : Enfrentando a Extinção, Defendendo a Vida

- Enfrentando la Extinción, Defendiendo la Vida (Español)

- Peluncuran video baru dalam Bahasa Indonesia : Menghadapi Kepunahan, Mempertahankan Kehidupan