Philippine palm oil plan ‘equals corruption and land-grabbing,’ critics say

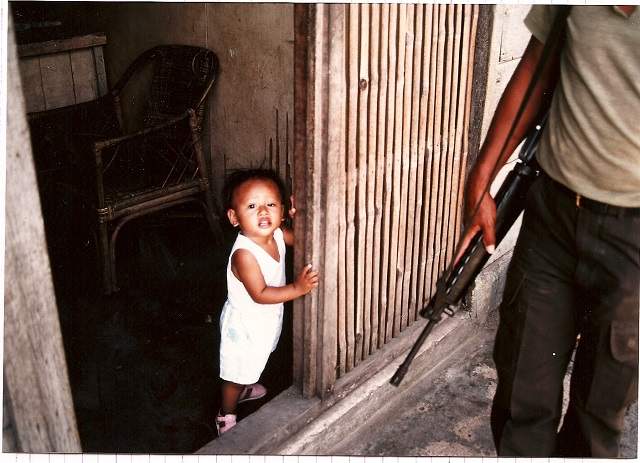

Soldier and child in the Philippines (Photo credit: Brad Miller / Mongabay)

DAVAO CITY, Philippines – If the street Pedro Arnado was looking down was on the Philippine government’s roadmap for future palm oil development, critics say it would be one highly dangerous to navigate, lined with the hazards of unfair labor practices, land poverty, militarization and environmental degradation.

Arnado is the Secretary General of Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (Peasant Movement of the Philippines) in Southern Mindanao, or KMP, and a spokesperson for the Farmer’s Association in Davao City. On January 26, 2017, he stood on the edge of a crowded rally of peasants, trade union members and indigenous people at Rizal Park in Davao City, Mindanao, describing how the palm oil industry has affected the farmers and communities in other provinces of Mindanao where plantations have already been operating. He says that the business-oriented development of palm oil “equals corruption and land-grabbing.”

While several palm oil plantations had been established on the island by the 1960s, it was what observers describe as an atmosphere of impunity born of the 1972-1981 period of martial law imposed by President Ferdinand Marcos that allowed corporations to increase their land acquisition, allegedly through coercion or force using the military and private armies.

Palm oil is produced from the fruit of the oil palm tree. (Photo credit: Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay)

During her term as president, which lasted from 2001-2010, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo continued to facilitate the growth of the palm oil industry, pushing through the Biofuels Act of 2006 and legislation that gave corporations tax holidays and fiscal incentives.

Now, with its renewed promotion of what it calls the “Sunshine Industry,” the Philippine government is looking to cultivate another one million hectares of oil palm, 98 percent of which would be on the island of Mindanao. They are promising the alleviation of poverty and armed conflict through large investments from Malaysian, Indonesian and Singaporean firms and other foreign and domestic companies, as well as the revenue brought by palm oil’s increasing demand as a food and cosmetic ingredient and biofuel.

‘They fear displacement’

In its “Philippine Palm Oil Road Map 2014-2023,” the Philippine Coconut Authority, which is the government body overseeing palm oil production, foresees that 300,000 farmers will receive benefits like jobs, schools, health care and housing due to the cultivation of new oil palm plantations covering 350,000 hectares by 2023.

In 2014, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, then mayor of Davao City, tried to persuade the communist New People’s Army (NPA) to drop their opposition to the development of a 20,000-hectare oil palm plantation in Paquibato, Davao’s poorest district. He reportedly even offered the insurgents the opportunity at something resembling a joint venture. But due to the continuing conflict in the area, the Malaysian investments were scrapped.

“The plan to plant palm oil was absolutely stopped,” Januario Bentain, Officer in Charge of Industrial Crop Coordination for the Davao City Agriculture Office, told Mongabay during a January 2017 interview. “The NPA don’t like that palm oil be implemented in the area.”

In their newsletter Ang Bayan, the NPA said they are still fighting the government after 48 years because: “Agrarian revolution is the movement’s key solution to widespread landlessness and land starvation in the country.”

But palm oil development in the Paquibato District was stalled for reasons other than peace and order and insurgency.

“The people are not receptive to the plan,” says Chibo Tan, Regional Coordinator in the Davao area for the National Federation of Labor Unions (NAFLU), an affiliate of the progressive labor umbrella organization Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU). “They fear displacement.”

A new push for palm oil

With the government holding intermittent peace negotiations with the NPA and their political wings, President Duterte is back pushing for investment in palm oil as an antidote to poverty and violence. After a two-day visit to Malaysia in November 2016, Duterte stated that foreign investors are once again ready to put their money into palm oil plantations in Mindanao, and that the vast quantity of unplanted land in Paquibato is a suitable locale.

The oily insides of an oil palm fruit. (Photo credit: Mademoiselle Galorio)

The new push for palm oil expansion in Mindanao is coming not only from the national government, but at the local level, with the Vice Mayor of Davao, Duterte’s son Paulo, and a number of City Councilors advocating new operations. It was reported in the local press as recently as March 2017 that the Davao City Chamber of Commerce and Industry has been working with the DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) to establish agribusiness ventures in the districts of Paquibato and Marilog, including palm oil, that have been designated as CBFM (Community Based Forestry Management) lands under the city’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan. The CBFM program was ostensibly created in 1995 to encourage reforestation.

The KMP’s Pedro Arnado says there are currently ongoing talks between investors, the city government and the tribal leaders of the local indigenous peoples (called IPs or Lumad).

Regionally, economic development has been encouraged under the Davao Integrated Development Plan, a blueprint for the city and four surrounding provinces that “pursues external market-driven development” and established Davao City as the “Southern Gateway” for foreign investment.

To create a feasible environment for economic development, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) has maintained a strong presence in the hinterlands of Davao, with combat and civilian-military operations conducted by the 11th Infantry Division. The AFP has also promoted a counter-insurgency strategy based on the U.S. Armed Forces Montangard program in Vietnam, initially through the government agency PANAMIN (Presidential Assistance for National Minorities), where local IPs are recruited, trained and armed to fight the NPA. Tribal issues are now handled by the NCIP (National Commission on Indigenous People), according to Major Medel Aguilar of the 5th Civil Relations Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. Aguilar told Mongabay that the AFP designates an officer to run the IP Desk for handling military-Lumad relations, facilitating their “Peace and Development” scheme—where the ancestral domain is “cleansed” of NPA to allow business enterprises to enter and purportedly elevate the economic level of the community.

Pro-business tribal leaders have been criticized by progressive IP organizations for being puppets of the military, having armed their followers under the military’s Lumad Cafgu (Civilian Armed Forces Geographical Unit) program. Some of these militia have turned into what are called “Alamara”—private armies that have reportedly run amok and taken to cattle rustling and looting villages. Jun Cajes, Chief Investigator at the government’s Commission on Human Rights, says this has divided native communities; some are joining the Lumad militias, others are opting to fight with the NPA.

Some worry the country’s palm oil expansion will result in increased militarization. (Photo credit: Brad Miller)

In addition to the Davao region, foreign firms are also interested in investing in the provinces of Agusan del Norte, Davao Oriental, North Cotobato, Sultan Kudarat and in the ARMM (Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao). A Malaysian firm, Alif-Agro Industrial Inc., has reportedly made plans for a $1 billion project in Agusan del Sur that would include a 128,000-hectare plantation, refinery and wharf. The Director of the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) wants to see the area designated an economic zone so corporations can take advantage of the available fiscal incentives and tax holidays.

Farmers are skeptical

Plans like this trouble people like Jay Legapa, a member of the NAFLU-KMU and palm oil harvester at Filipinas Palm Oil Plantations, Inc. (FPPI) in Agusan del Sur, whose says his father has been waiting 30 years to receive his plot from the agrarian reform program.

“How will we get our land if the dream of the President is funding the palm oil industry?” he asked during an interview with Mongabay in March 2017.

But not all government officials are backing the expansion of palm oil plantations. Marissa Salvador-Abella, a Davao City councilor who is also the chairperson of its Agriculture Committee, says she is promoting a strategy that stresses diversified crop development, including the cultivation of organic cacao, coconut and abaca. Salvador-Abella, whose constituency includes the residents of Paquibato, would also like to see more involvement of the local Lumad community in any projects, as well as the construction of more farm-to-market roads.

Koronado Apuzen, Executive Director of the Foundation for Agrarian Reform Cooperatives in Mindanao (FARMCOOP) concurs that people will “earn more from a diversified farm.” He says that since palm oil needs a large amount of land, it is the big companies that will benefit.

“Palm oil is not good for the farmer,” he told Mongabay in February 2017. “It will impoverish them further.”

Palm oil proponents stress the potential for job creation and benefits such as health insurance for the workers. But environmental groups like Panalipdan Southern Mindanao fear that the expansion of palm oil will continue to bring a decline in rice and corn production; they say rice harvests have already fallen by 21 percent in the Davao area. They are also concerned that fertilizers and pesticides applied by the plantations could pollute the watersheds that provide water for Davao City. The International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP) has cited that the palm oil industry uses chemicals such as carbofuran, glyphosate and paraquat, which it says pose a threat to the plantation workers applying them and to the communities they live in. The Pesticide Action Network includes paraquat on its list of highly hazardous chemicals, linking it to health problems like skin cancer, Parkinson’s Disease and respiratory and kidney failure.

Victor Sanugan, a farmer in Kalabugao, Bukidnon, voiced his concern during a March 2017 interview that the palm oil firm A Brown Energy and Resources Development, Inc. (ABERDI), which was operating in his community under its subsidiary Nakeen Corporation until a suspension of work in the summer of 2016, is using pesticides that are having negative impacts on water, livestock and plantation workers. Mongabay contacted A Brown concerning Nakeen’s use of these chemicals several times by e-mail, but had received no response by press time.

Environmental repercussions

A number of environmental entities have raised doubts about the benefits of cultivating palm oil to produce biofuel. A study conducted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency concluded that biodiesel produced from palm oil does not meet the minimum lifecycle greenhouse gas reduction threshold needed to qualify as a renewable fuel, and therefore will not significantly reduce carbon imprints. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the conversion of forests to agricultural land, especially in the tropical regions of Asia, accounts for approximately 14 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Many conservation and scientific organizations, such as WWF, also cite a direct correlation between the expansion of palm oil plantations and deforestation.

Deforestation for palm oil in Sabah, Malaysia. (Photo credit Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay)

In 1900, 70 percent of the Philippine archipelago was covered in forests, but the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) estimates that only 24 percent remained by the early 21st century. Primary – or old growth – forest cover is lower still; according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, 11 percent of the country’s primary forests remained as of 2015.

The consequences of denudation have been the loss of biodiversity, the erosion of topsoil and devastating floods and landslides, which the Haribon Foundation says has caused over 10,000 deaths and the displacement of close to one million people since 1991. The palm oil-producing provinces of Agusan del Sur and Misamis Oriental were hit by a devastating round of floods during the winter of 2017. Since the DENR passed a directive in 2004, oil palm has qualified as a reforestation species, but its effectiveness at mitigating erosion is a source of controversy.

“It is better than nothing,” says Januario Bentain of Davao City’s Department of Agriculture. But FARMCOOP’s Koronado Apuzen thinks people would rather be planting trees than crops like oil palm. He says oil palm planted as a mono-crop in mountainous terrain that dominates areas like Paquibato are a leading factor in erosion, cautioning that “if you destroy the forests, you reap the reward—that is disaster.”

An uncertain future

Shortly before the annual May 1 Labor Day rally in Davao City, the KMP’s Pedro Arnado outlined an alternative path to the palm oil industry’s road map. In what he termed an “agrarian revolution,” the Genuine Agrarian Reform Bill (GARB) would be passed and implemented. The GARB would not just give land back to the tiller, but would require the government to supply them with the technical support, water and fertilizer he says are currently lacking in order to become productive.

The KMP stated in an October 2015 press release that if the government continues on its proposed plan to auction off one million hectares of land to local and foreign palm oil corporations, “political unrest and people’s resistance in Mindanao will continue to intensify.”

After President Duterte declared Martial Law in Mindanao in May 2017, the KMP’s chairperson Joseph Canlas added in a separate statement that “the militarist path taken by the government will never address the root causes of the worsening social and economic turmoil, armed conflicts and unrest in the countryside” and that “farmers will continue to assert and defend their democratic, civil and political rights even under Martial Law.”

Source: mongabay.com

Related Project:

Territories of Life

The Territories of Life toolkit is a series of 10 short videos that share stories of resistance, resilience and hope with communities on the front-line of the global rush for land. These videos, available in English, Spanish, French, Indonesian and Swalhili and are currently being disseminated widely by community facilitators.

Categories

Latest news

- LifeMosaic’s latest film now available in 8 languages

- การเผชิญหน้ากับการสูญพันธุ์ และการปกป้องวิถีชีวิต (Thai)

- LANÇAMENTO DO FILME BRASIL : Enfrentando a Extinção, Defendendo a Vida

- Enfrentando la Extinción, Defendiendo la Vida (Español)

- Peluncuran video baru dalam Bahasa Indonesia : Menghadapi Kepunahan, Mempertahankan Kehidupan